@senjisilly just now saw your reply. Thanks for the pedigree website. I knew about it and it’s a great resource.

What does it mean to add genes?

-

My apologies for taking so long to return to this thread. My schedule and workload has kept me away from the Forum. I hope we can continue this discussion, which I think is very important.

Thank you for the gentle reminder that was sent privately.

To refresh my memory, I have just gone back and quickly skimmed through the discussion. Wow, so many good comments!

I am trying to attach a picture with my comments. Please bear with me …

-

I checked in the FAO's and see that it is possible to attach a file (a picture from my computer) to my post through the 'New Post' option. But, I don't see how to do that.

Can anyone explain how for me?

Thanks,

-

http://www.suite101.com/content/central-africas-dog--congo-origin-of-the-basenji-a224967

For this post, I have chosen to avoid using the label "Basenji" for the native dog because that serves only to distract and confuse people who get hung up on something that is no more than a Westernized word.

As a professional who continues to spend most of my adult life analyzing and studying the biomes of Africa and the variation of animal types across landscapes as well as living and working on the continent for 20 years, I would like to comment. I bring to this discussion a career of looking at the geographical distribution of animals at different taxonomic levels across Africa. Based on my extensive research, training, experience, and education, I thought we could look at this from a bit of a different perspective ... a perspective focused on selection pressures/ processes and the mechanisms / barriers that have regulated gene flow over the past 2,000 years (not including the recent 200 years), which includes ethnicity (tribalism), culture, language, geography, technology, logistics, history, environment, etc.

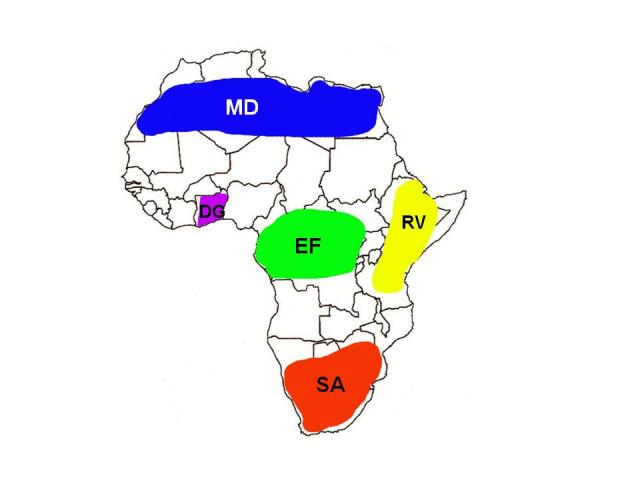

First, let's consider the geographic location of different biomes. A biome is simply any major ecological community of organisms, both plant and animal, usually characterized by the dominant vegetation. Biomes are defined in terms of the entire biotic community of living organisms and their inter-relationships with their immediate environment. To this end, I have attached an illustration of the most dramatic biomes of Africa that we might want to consider hypothetically for this discussion. These biomes have a direct and significant impact on the biotic (plant and animal types) assemblage available and the human lifestyles (including how the dogs are routinely employed) that evolved in each region.

The polygons illustrated are representative of some of the most distinct overall regional ecosystems on the continent :

MD = desert south of the Mediterranean ;

DG = Dahomey Gap ;

EF = Equatorial Old-growth Forest ;

RV = east of the Rift Valley ;

SA = Southern African countries.

All aboriginal (original or earliest known domesticated) dogs have a very similar morphology. The primitive canid body shape is known as the "long-term pariah morphotype" (LTPM). The LTPM silhouette is characterized by a "wolf or fox-like appearance, with sharp-pointed, erect ears, a long, pointed muzzle and a long, fish-hook shaped tail." This is the generalized form that is at the root of the domestic canine ancestry.

Before humans selectively bred for conformation, the earliest dog ancestor diverged into populations of separate types based on natural selection (including the mechanisms identified above) and their abilities to function in each biome.

Over the past few thousand years, each geographically specific variety of dog (with a distinctive common gene pool, consistency of type/ appearance, and consistent function) evolved from the basic / original LTPM form into a recognizable, visible type, landrace breed. The resulting distribution of general breed types are specific to their biome of origin.

This is one of the first points I would like to make. So often I read people referring to dogs that are "basenji-like" in that they have a common general silhouette.

What I believe they are actually observing is the LTPM starting place. It can be seen in all the primitive, aboriginal breeds : Australian Dingo, African Basenji, Canaan Dog, Carolina Dog, New Guinea Singing Dog, etc. But, "basenji-like" is NOT necessarily Basenji.

Given this background of landrace breeds specific to their biome, for the purpose of this discussion I can identify a unique type (breed) that will be called "EFb" (i.e., Equatorial Old-growth Forest breed) because it originates in the EF biome. EFb, as with the other landrace breeds, began with a primitive canid body shape thousands of years ago. Over those passing thousands of years, once the LTPM was introduced into the EF biome its form evolved into the distinct breed type recognized by early Westerners as the Congo Terrier (= EFb).

lvoss started this thread in order to discuss genetic diversity as it applies to the importance of adding Native Stock to our breed to provide "new genes." But, what do we really mean by needing to "add" genes to the breed (outside the EF biome of origin)?

One of the principal arguments for adding additional native stock to our registered breed is to expand / increase genetic diversity. But what does that really involve?

Possessed within the EFb population in their biome of origin we find the full breed complement of genes distributed across each individual EFb genome. Some individuals have some genes and others have others but together they have all the genes that make up the distinctive genetics of the EFb. It is that EFb genome at the population level that holds the maximum degree of genetic diversity.

Basically what we have is the wolf-dog common ancestor with the most diverse genome. As the population split / diverged, those that became the LTPM (primitive / original dog) had less diversity in the original genes (those from the wolf/dog genome) but added diversity through mutations, ect. As the LTPM were established in the various biomes, each discrete population diverged from the LTPM into distinct types associated with the biomes where they adapted to the regional conditions. Each of those types was genetically less diverse than the LTPM common ancestor but also gained "new" and different genes through the processes of evolution. [BTW, evolution through natural selection / natural processes does not happen over decades but requires thousands of years.] So, we ended up with different "breeds" (each consistent in type and with a distinctive population genome).

Side-track Note : Consistent in type is not the same as cookie-cutter phenotypic clones.

This can be illustrated with two examples.- A writer/photographer team from National Geographic came to my Congo base to write an article that had nothing to do with dogs. In fact, we had never even mentioned anything about the dogs. But, as we arrived in the villages, the NG team openly commented (without any prompting or even mention about dogs) : ?What breed of dog is this?? My astonished response was ?Why do you ask that (in those words)?? and they said ?They all look exactly alike!? Even laymen who have no background in the world of purebred dog breeds could identify the visible uniformity and consistency of type. But, they did not have the discriminating eye to distinguish the variation of individuals.

- Before we bred any of my native dogs, I had a long-time breeder visiting who has been breeding for several decades. They were very impressed with my dogs as purebred Basenjis. There was never any question about the purity of my dogs as Basenjis. The breeder spent many hours with my dogs, watching them and handling them intimately. When the breeder went home, they contacted me to tell me how taken aback they were after spending the day with my pack and then seeing their own conformation-show-line Basenjis, how much our breeding practices have made the breed into match-stick dogs, cookie-cutter clones.

Back on track : So a dog from the very heart of the EF biome would potentially contribute "new" (as in new to the Basenji gene pool outside the biome of origin but not new to the EFb gene pool) genes that are found within the original EFb population genome.

The question that the Basenji fancy must answer is do we want to add genes from any dog population across Africa which will potentially add "new" genes because other populations (for example, the MDb or DGb or RVb or SAb) have some different genes not found in the EFb ... essentially outcross to a different landrace breed. Or do we want to add genes from within the EFb genome?

Somebody said it already : We want new and diverse BASENJI GENES [the EF population genome]. That is the crux of it all.

If the fancy chooses to include any African dog that exhibits the LTPM silhouette because it offers different genes, then I agree that our breed will be no more than an African village mongrel and does not reflect its unique ancestry or origins. That is the choice the BCOA members must make.

And a related point that was made in this thread : sharronhurlbut asked, "Wouldn't the point of being able to add more, to allow folks who have gone to Africa or new folks to go, to check out different areas that maybe aren't open now?"

This is a critical statement. The value of adding additional native dogs to access other EFb genes only comes from adding dogs within the EF biome from areas not already represented by current founders. To continue bringing in dogs from the same geographic area(s) within the EF biome does not add "new" genes or contribute to gene diversity.

DebraDownSouth posted that we have 26 founders (as stated in my article published in 2007). However, since that article was published we have added 15 founders. So, we are now up from 26 in 1990 to 41 native dogs registered with AKC as Basenji breed founders in 2011. Of those 41 dogs (with varying degrees of representation in the gene pool), 20 come from the same area. That is contraindicated in the argument for adding gene diversity.

When we state the number of founders, the assumption is that each founder is equally unrelated to any other founder in the population except their descendants according to their pedigree representation. Our reference number does not take into account the degree of relatedness. There a mathematical calculation that can be used to determine the proportion of genetic material contributed to the current population by each founder by comparing a target representation with actual representation. Negative values denote founder over-representation. This requires that we decide what target level of representation is acceptable for breed preservation.

Has the breed changed since we established it outside its biome of origin?

My example above might suggest that we have now created a different (some might say "improved") phenotype. But, I would argue that does not take into account the full spectrum of AKC registered Basenjis that do not appear in the conformation show ring.

Further, I think it is very important for us to consider whether the Basenji at the source (the EFb, for the sake of this discussion) has changed. Here I refer you to pictures from the website linked in my signature line. On the Lukuru Basenji Conservatuers website home page there is a black&white picture of my four native imports in 2009 and a comparable black&white picture of five "Of the Congo" dogs in the late 1930's. Even after 70 years, it is striking how similar my native imports resemble F1 generation from the original imports. In fact, both my husband and I had to take second and third looks at the old picture because it looks so much like our dogs. In this case, I think the evidence indicates that in some areas within the biome of origin the EFb of today is uniform and consistent with the EFb of yesteryear when we first established the Basenji as a registered breed.

-

The numbers I have seen done by people in the breed shows that we have lost roughly 50% of our founders. That includes just from the new imports in 87/88, which is only just over 20 years ago, and already we have lost 50% of them and some only trace back to one or two breedings or 1 or 2 offspring.

This brings us back round to Clay's point, what good is it to open the stud book to foundation stock if there is no longer plan for incorporating them into the gene pool. If BCOA wants a successful native stock program then it should also include educational opportunities to learn how to best make use of the native stock otherwise people will just dip in once and then breed away from it and get the "feel good" sensation of doing something good for the breed when in fact they have done nothing.

Genetic diversity in the Basenji breed has long been an issue that interests me. I have often wondered what is really happening in our breed to reduce gene diversity? Does bringing in additional native stock actually impact the gene diversity of the breed?

lvoss has been asking similar questions in this thread.We know that historically the Basenji breed has suffered significant bottlenecks that contribute to loss of diversity in the gene pool.

In the first 25 years of the establishment of a breed we call Basenji (between 1936- 1961), 18 individuals who contributed unequally to the gene pool were the foundation of the breed (9 dogs & 9 bitches). Three of these were outcrossed Liberian camp-dogs. The record reveals that the Liberian camp-dogs were subjected to a controlled breeding program for more than 12 years selecting for "Basenji" traits. Only then did the get of this intensive selection effort become recognized as outcross founders. In fact, the results of the breeding program produced dogs that were exported to Zambia to be bred with purebred, registered Basenji bitches (bred down from Congo native stock) brought from England. Then those get were imported to England by Elspet Ford and to the USA by Gwen Stanich. Although they are considered to be native dogs because they were whelped in Africa, they were actually only a percentage African stock.

There were no Liberian imports (native Liberian dogs) registered as Basenjis. By the time the dogs were imported, they were heavily blended with Congolese dogs BEFORE the progeny were included in the breed registry. This outcross was done simply because some members of the fancy wanted the dominant black coat color. Once the dominant black & white was bred with Basenjis from England, there were never any back-crosses to native Liberian stock.This is a perfect example of the comments by lvoss. Her important premise is that in order to have a significant impact, new dogs have to be desirable to breeders and the fancy. They have to contribute something positive to the breed. In the example of above, the contribution from outcrossing to Liberian dogs was the dominant black coat color.

Similarly, the example of the Congo dogs registered in 1990. The contribution they made to the breed was the brindle coat pattern. Although subsequently we can say that they also provided new breeding opportunities to steer away from fanconi; we did not know that when the dogs were imported and that was not a goal of the importation effort in 1987/1988.Anyway, the founder effect severely reduced the genome (frequency of genes in the population) of what had been the genetically diverse EFb geographic breed.

Drastically narrowed, only the genome of the dogs used to start the breed served as the genetic foundation of the dogs named Basenji by Westerners. In this way, a gene quite rare in the EFb population may have a much higher frequency in the Basenji population; conversely, genes common in the EFb population may be infrequent or even absent from the Basenji population. We can never know what we lost or what we disproportionately magnified in the genome of the Basenji compared to that of the EFb.Of course, that wasn't the end of the story nor was the door closed on including other EFb genes. In 1990 and in the recent two years, additional native dogs have been added to the foundation gene pool. But, the Basenji genome is still based on a small number (subset) of individuals and can never represent the EFb genome.

Several years ago a breeder interested in finding unrelated lines to use with her own line did a pedigree analysis. By studying a sample of dogs that might be of interest and were "unrelated" to her own lines, she found three significant bottlenecks and extrapolated her findings to the wider gene pool of the breed.

First, from her sample she concluded that the US Basenji gene pool was approximately eight significant foundation individuals. The foundation stock who had contributed most to the breed were :

Bongo of Blean (male)

Amatangazig of the Congo (female)

Bereke of Blean (female)

Kindu (male)

Kasenyi (female)

Fula of the Congo (female)

Bokoto of Blean (female)

Wau of the Congo (male)

Second, Basenjis in the US show a second significant genetic bottleneck through disproportionate use of the OTC suffix (Of the Congo) dogs. During World War II Veronica Tudor-Williams was foremost in preserving the breed at a time when the Ministry of Home Security required the compulsory destruction of all dogs. There were a handful of other breeders that maintained lines, but it was VTW who bred prolifically and exported her OTC dogs to the USA.

Third, Basenjis in the US had a significant genetic bottleneck in the 1960's and 1970's due to the use of three popular sires, two of whom were sons of the third.Without knowing about that analysis, a number of years ago I inquired about the Basenjis that were used as the basis to make conclusions about the Basenji Genome in all the genetic research into breed origins. From that information I was able to determine that genetically Basenjis are derived (for the purpose of research) from only six founders :

three foundation sires -

Avongara Gangura

Kindu

Wau of the Congo

and three foundation bitches -

Avongara N'Gondi

Avongara M'Bliki

Amatangazig of the CongoAnd a couple years ago I initiated a game on one of the Basenji chat lists to track tail male and tale female lines. This was a simply and fun exercise to illustrate a singular aspect of founder loss in our current population (it does not reveal what is happening in the middle of a pedigree nor loss of genes on the autosomal chromosomes). So, it does have limitations. But it can reveal when a founder no longer has descendants; i.e., the founder is lost to the breed and all the unique genes the founder contributed. At that time it appeared to me that there were quite a few breeders who believe that each kennel name represents a distinct genetic line. The exercises was not only fun and easy with minimum instruction, but it illustrated to many that genetic diversity is NOT determined by the number of kennel names.

These examples give us important insight into the use of native stock in our breed; the overrepresentation of individuals in the breeding program, loss of some unique breeding lines, and illustrate how much our gene pool has narrowed.

Concerning the erosion of the gene pool, it is important to know how many founders are still represented in the current Basenji population and to consider the number of generations our current dogs are away from the founder. In genetically limited populations, a certain amount of unique genetic diversity is diluted with each reproductive event through the action of genetic drift, inbreeding and artificial selection. Thus, the number of generations away from the founder becomes an issue of concern. Genetic material can be rapidly narrowed, each generation carrying a reduced level of heterozygosity as it is permanently linked by the horizontal pedigree. The average time between one generation and the next is a convenient yardstick to help us realize the relative rate of genetic attrition.So, I still wonder if admitting new native stock EFb into the Basenji gene pool will actually help gene diversity in the long run.

I keep going back to the article by Mary Lou Kenworthy, "WHAT IS DIVERSITY REALLY?" (The Modern Basenji Worldwide, Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 2011, page 3) and Mary Lou's statement, " If breeders create and monitor their own lines, the breed, as a whole, will prosper. No breeder can maintain diversity by himself, and any attempt to do so will lead to disaster for the breeder and the breed. It takes a network of breeders working together with individual lines to maintain diversity. "

I think she is correct.

-

Jo,

Thanks for taking the time to provide so much thought provoking detailed information. I almost missed a meeting because I was so engaged reading all of it, lol. I know I have several questions but I'll have to wait until after work to ask them.

Clay

-

Jo,

Thanks for taking the time to provide so much thought provoking detailed information. I almost missed a meeting because I was so engaged reading all of it, lol. I know I have several questions but I'll have to wait until after work to ask them.

Clay

Thanks Clay! Just in case your computer presented my two posts on different pages … I posted two long comments this morning. The first with an attached figure appeared on page 6 of this thread and my second this morning appeared on page 7.

-

I know the situation is different in the UK but I find this thread extremely interesting and of course much applies to our UK population.

I am having to print your posts - for my own information - Jo because I find it difficult to read off a computer - I hope I have your permission?

-

I am having to print your posts - for my own information - Jo because I find it difficult to read off a computer - I hope I have your permission?

Yes. Of course.

-

Thank you for this Jo. I will be rereading it until I am sure I "get" it all.

-

I think it might be useful to post some information about preserving land race breeds. My primary source when researching this over the years has been Dr Phil Sponenberg, a geneticist and professor at Virginia Tech’s vet school, who is a specialist on preserving rare and land race breeds.

I’ve also gotten useful insights from Species Survival Plans, but IMHO Sponenberg is both more applicable and presents more practical applications. FYI, Dr Sponenberg is scheduled to speak at the 2012 National, which should give Basenj fanciers a useful opportunity.

Sponenberg has advised many breeders, in many species, on how to preserve their breeds. One frequently asked question is what to include in the registered breeding pool. His principle is simple. Include as many animals as possible of that breed, and do not include those that are not of that breed. He has a fairly detailed discussion of this, with examples, in his last book, Managing Breeds for a Secure Future, which is available from Amazon and from the ALBC. See particularly pages 20-23.

As far as gene loss goes, Boyko’s work on genetic diversity in Basenjis versus village dogs shows very significant reduction in genetic diversity using microsatellite markers, with about .356 for Basenjis versus .553 to .684 for various populations of village dogs.

Bringing in new individuals from the same geographic areas does add new alleles (versions of genes – all dogs have the same genes - just different versions of them) and does contribute to genetic diversity. In many land race breed populations, all of the individuals may come from a relatively narrow area (Soay sheep, Shetland sheep, Fjord horses, and Icelandic horses all spring to mind) but there can be significant genetic diversity within the parent population in any given location, that requires a fairly large number to sample thoroughly.

In general, a minimum of 100 founders is given, and I have heard 200 bandied about as a more desirable minimum number. In practical discussions of preserving land race breeds, I have never seen an expectation that founders be unrelated – all members of a land race breed, or any breed, are expected to be related – but rather terminology used that founders are the individuals where known pedigrees stop.

Increasing diversity in the gene pool was a major driver in the 1980’s importations, per people who went. Dr Russ Brown, a geneticist from Virgina Commonwealth University, contributed to the petition to open the stud book, contributing from that perspective. Russ lived near where I worked, and was the breeder of my Ch JuJu’s Pistol Pete. I understand that some people do not realize these dogs were imported to expand the gene pool, but Russ was quite definite about it.

-

Avongaras have made a significant impact on the gene pool, and not in the sense of one cross and quickly breeding away from. A number of long time breeders breed straight Avongaras. I was able to come up with a dozen serious breeders that have recently bred full Af litters, plus probably half again that many people working with them (ie, own one or two Avongaras that they keep intact, and work with the group.) Plus the overseas people.

Of the dozen I thought of right off, they’re pretty much all working together to a greater or lesser degree. The goal is to maintain an outcross gene pool, of good type and quality, which does offer significant value to the breed.

Newly imported Avongara stock would be particularly useful in maintaining a viable outcross group for the longer term, and some of the newer Avongara imports have already been incorporated. Others (like the ones in the nice pix Katie and Ethel had) show a lot of promise.

Most of the breeders I know using Avongara blends are not using one outcross and then diluting – they are using significant percentages of Avongara stock. Good examples from my region include the #3 producing brood bitch of all time, Ch Eldorado’s Ooh La La (38.625% Avongara from 3 separate crosses that incorporate 5 different Avongara founders.)

Or you can look at a stud dog I have used, Ch Wakan MicCookie http://www.wakanbasenjis.org/Micki%20collage%20jpg.jpg 31.25% Avongara and his littermate Ch Wakan Sugar Cookie http://www.wakanbasenjis.org/SugarCollage.jpg

My own favorite brood bitch, Itzyu Good Golly Miss Molly (call name Sally, long story), is 50% Af – the result of breeding two good half Afs together – dam of some very nice pups, with one ready to go out and on my FB page, and two on deck. The latter two are about 35% Af, from breeding to a dog that is 19.3125% African, with pups that are about 35% Af. The pups go back in 5 different lines, with each line going to one or more of five different Avongaras (Gangura, Diagba, Zamee, Mbliki, and Ngola.) It’s not cross once and out – it’s blend, and blend back, and blend back again.

I have full Afs in my kennel that also go back to Kposi and Elly, plus breeding rights on a Tambura kid (or possibly kids, another long story) and Renzi is also represented in my part Afs and in a number of dogs in this area.

These dogs have pedigrees that have been, and are being, used by many different breeders. Of the 87/88 imports, most of what got lost, was lost the first generation (Wele died in an accident, Renzi went sterile after one litter although his kids were used and are in a good number of Virginia pedigrees, Nabodio was in a pet home and did not produce pups when he was used as an older dog, one was not bred by choice, and one had pups with bite issues and was not bred down from.)

Diagba, Gangura, Zamee, Mbliki, Ngola, Elly, and to a lesser extent Kposi are pretty well represented in the gene pool – even Kposi, which is the rarest of the bunch, has full Af descendents with some linebreeding to her going on. I have dogs here that are 25% or more Gangura, Zamee, or Elly – just lost a Kposi grandson who has multiple kids in the gene pool - and there are many dogs out there that are 25% or more Mbliki or Diagba.

-

Sponenberg has advised many breeders, in many species, on how to preserve their breeds. One frequently asked question is what to include in the registered breeding pool. His principle is simple. Include as many animals as possible of that breed, and do not include those that are not of that breed. He has a fairly detailed discussion of this, with examples, in his last book, Managing Breeds for a Secure Future, which is available from Amazon and from the ALBC. See particularly pages 20-23.

Itzyu, I'm glad you joined the discussion.

Without having easy access to the book to read about the bolded sentence, can you paraphrase what comments he has on how "animals of that breed" and "animals not of that breed" can be defined? I think that gets to the crux of some of the issues discussed here.

Without having easy access to the book to read about the bolded sentence, can you paraphrase what comments he has on how "animals of that breed" and "animals not of that breed" can be defined? I think that gets to the crux of some of the issues discussed here. -

Avongaras have made a significant impact on the gene pool, and not in the sense of one cross and quickly breeding away from. A number of long time breeders breed straight Avongaras.

Diagba, Gangura, Zamee, Mbliki, Ngola, Elly, and to a lesser extent Kposi are pretty well represented in the gene pool ? even Kposi, which is the rarest of the bunch, has full Af descendents with some linebreeding to her going on.

Can you help me understand your definitions of the above? I think that would be a useful context to further the discussion. What is a "significant impact" or what is "well represented"? This would help me understand the different perspectives on this.

-

Itzyu, I'm glad you joined the discussion.

Without having easy access to the book to read about the bolded sentence, can you paraphrase what comments he has on how "animals of that breed" and "animals not of that breed" can be defined? I think that gets to the crux of some of the issues discussed here.

Without having easy access to the book to read about the bolded sentence, can you paraphrase what comments he has on how "animals of that breed" and "animals not of that breed" can be defined? I think that gets to the crux of some of the issues discussed here.It's really good to get the book - well worth buying and I strongly recommend it for anyone interested in Basenjis or any other land race breed of any species. See www.amazon.com or the ALBC website.

That said, ALBC has their books online at Google Books and you can read pages 20-23 at http://books.google.com/books?id=GmsDwDuuP2cC&pg=PT100&lpg=PT100&dq=sponenberg+preserving+breeds&source=bl&ots=6RiX-84Svh&sig=LZhXlf8_auMwBfmuShgk9nDfVTY&hl=en&ei=EWtMTti5Ls25tgelib28Cg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBYQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

Sponenberg says it better than I can, and the whole section - heck, the whole book - is worth reading.

-

It's really good to get the book - well worth buying and I strongly recommend it for anyone interested in Basenjis or any other land race breed of any species. See www.amazon.com or the ALBC website.

That said, ALBC has their books online at Google Books and you can read pages 20-23 at http://books.google.com/books?id=GmsDwDuuP2cC&pg=PT100&lpg=PT100&dq=sponenberg+preserving+breeds&source=bl&ots=6RiX-84Svh&sig=LZhXlf8_auMwBfmuShgk9nDfVTY&hl=en&ei=EWtMTti5Ls25tgelib28Cg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBYQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

Sponenberg says it better than I can, and the whole section - heck, the whole book - is worth reading.

Thanks, I can't preview those pages but I will definitely add it to my wish list.

-

Can you help me understand your definitions of the above? I think that would be a useful context to further the discussion. What is a "significant impact" or what is "well represented"? This would help me understand the different perspectives on this.

I think that is going to differ depending on who you talk with - but to me, a significant impact is when dogs are recognized as being useful in the gene pool to enough people that they are likely to have a lasting influence.

Well represented, to me, means descendents are in multiple households, appear likely to breed on, and are not limited to one or two people or one or two small programs.

They tend to go together, for obvious reasons, but aren't exactly the same thing.

-

Thanks, I can't preview those pages but I will definitely add it to my wish list.

Try using the right hand scroll bar - it should let you scroll all the way up. At least when I browsed it, I was able to read that section.

-

Try using the right hand scroll bar - it should let you scroll all the way up. At least when I browsed it, I was able to read that section.

It's just letting me preview a different section of the book, pages earlier in the book than 50 are "omitted from this book preview." Just bad luck with Google Books. The section I looked is very interesting though. Definitely looks like a good book.

-

@JoT:

[

This is a critical statement. The value of adding additional native dogs to access other EFb genes only comes from adding dogs within the EF biome from areas not already represented by current founders. To continue bringing in dogs from the same geographic area(s) within the EF biome does not add "new" genes or contribute to gene diversity.Jo, my main question goes to this general statement. Practically, do these "areas not already represented by current founders" still exist and if so, are they accessible and relatively "un-compromised" (for lack of a better word) by dogs that may represent other areas in the EF biomes or elsewhere.](http://www.suite101.com/content/central-africas-dog--congo-origin-of-the-basenji-a224967)

-

I think that is going to differ depending on who you talk with - but to me, a significant impact is when dogs are recognized as being useful in the gene pool to enough people that they are likely to have a lasting influence.

Well represented, to me, means descendents are in multiple households, appear likely to breed on, and are not limited to one or two people or one or two small programs.

They tend to go together, for obvious reasons, but aren't exactly the same thing.

Thanks, I realize this all depends on perspective. It would be beneficial IMO if "significant impact to the breed" could be dimensioned in a more quantitative way. We seem to have ways to demonstrate "significant negative impacts" such as with the discussions of popular sires and their disproportionate contributions to the gene pool but "positive impacts" seems to be more nebulous to demonstrate.