@senjisilly just now saw your reply. Thanks for the pedigree website. I knew about it and it’s a great resource.

What does it mean to add genes?

-

I also encourage people to go through lots of old magazines and see how much diversity we have lost. If you compare Native Stock strictly to what is seen today, I think most people would be sorely disappointed. If you compare Native Stock to the natural variations observed in past decades, I think you will begin to see that some fall within the spectrum of expected characteristics and others clearly fall outside. The problem is that with the narrowing of the gene pool many are becoming less accepting of variation which will only serve to further reduce the genepool.

Maybe this is what the fancy needs education on, or at least a reminder of how much variation there used to be, or perhaps should be? Maybe now since more information about the breed history is being added to the BCOA website, new people will have access to the information, but I'm not sure the appreciation would be there. There would probably be a lot of value of an organized breeder mentoring program, particularly from this perspective.

-

And yet, wouldn't it be marvelous if the older folks took on a "guardian of the breed" view and dug in, dedicated a part of their breeding program precisely to saying–- okay not going to be winning for a generation or 2 or 3, but I'm helping the breed long term. Or if BCOA helped support more African percentage classes (ie 1/4, 1/2 and pure). I am not sure if AKC would allow such classes as part of their shows, or how it would work.

What my mind keeps coming back to is that there would need to be a vision of what they are trying to accomplish in the end (darn corporate america brainwashing :rolleyes:). If diversity is basically providing more choices, what does success look like? How many more choices is meaningful? How you know the breed is sufficiently more diverse than it was before? I like Quercus's suggestion around taking inspiration from the zoo world, I bet a lot information could be mined from there as well as other dog breeds.

-

I couldn't agree more. I would imagine that most breeders who have been doing this for twenty or more years might not be interested in a general 'breeding program education'; but maybe (hopefully) people who are newer, or reluctant to jump in might be. I think this is a really interesting idea Lisa, and one that should be seriously considered for the future.

raises hand I have only been breeding 19 years <vbg>but I would love to go to a seminar on this topic. True, I have strong opinions on some topics but I am open minded about new ideas that are presented in a logical manner. I would find this topic very interesting.</vbg>

-

Related to Dr Jo's comment on the other thread that prompted this one, I also keep getting the perception that the health of the breed is doomed and the only way we can save it is through importing native stock. I'm not sure where it comes from, maybe because I haven't been around this for very long at all.

I have grown weary with people using "health" as a reason to import new dogs. Thanks to the diligence of breeders from early on until present, the Basenji is one of the healthiest pure breeds there is. I do feel that importation can be important to the breed as a whole but not for the purpose of "improving" health.

People seem to forget that imports do not come with researchable pedigrees and therefore we have absolutely no idea of what health issues they could potentially carry. We got lucky with the Avongaras as they turned out to be quite healthy overall but it could easily have gone in the opposite direction.

For clarity, I am not saying imports are unhealthy, just that inherited health problems are an unknown factor for several generations, long enough for recessives to appear.

-

Lisa, thank you for starting this thread. It is fascinating and I am intrigued by people's perceptions and beliefs about this issue. In fact, there are many layers of important discussion points with this topic. I would like to see us vet many of them in discussion.

I apologize for not joining in sooner, but I've got an awful lot on my plate right now and only able to check in online intermittently. Even then, I only check here once in a while.

There has been a lot put forward in this thread and some very complex issues. I hope to come back throughout the weekend or early next week and comment on a couple of points that have been made.

But until then, for those interested in some excellent, thought-provoking reading, I strongly recommend that you take the time to go through a couple very good articles.In no particular order:

FROM THE EDITOR by Wanda Pooley, published in the BCOA Bulletin magazine, Vol. XLVI, No. 3, July/Aug/Sept 2009, page 3.

Wanda did an analysis of the number of Basenjis registered in the AKC stud book over the 10-year period 2000-2009. The numbers she presents illustrate a steady decline and a difference of 47.47% between years 2000-2009. This indicates a shrinking population of breeding stock.WHAT IS DIVERSITY REALLY? by Mary Lou Kenworthy, published in The Modern Basenji Worldwide, Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 2011, page 3.

Mary Lou comments that,

"the main problem [she] noticed is that most people try to apply population genetics to individual breeding programs and cannot separate the two in their minds."

She is a proponent for breeders establishing separate breeding lines. She says,

"If breeders create and monitor their own lines, the breed, as a whole, will prosper. No breeder can maintain diversity by himself, and any attempt to do so will lead to disaster for the breeder and the breed. It takes a network of breeders working together with individual lines to maintain diversity."IN DEFENSE OF BREEDING by Chris Maxka, published in The Modern Basenji Worldwide, Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2011, pages 6-7.

Chris addresses the belief that the "lack of diversity" mantra came into full throttle in the wake of the Fanconi Syndrome tsunami. Subsequently, AKC was petitioned to open the Stud book for new founders. She wraps up with the statement,

"A lot of good work has been done in many breeding programs, and we would not be helping the breed if we were to incorporate new imports with major flaws or of atypical type, for the sake fo the amorphous concept: 'diversity.' "

This article can be read online at -

<<<<>>>>>

Voodoo, apparently the Canine Genome Project has established the Basenji as the oldest domesticated breed and also that many of the others so claimed have actually been reconstructed.

When the 'originals' were imported to the UK they were brought in from areas where no other breeds of dogs were found - remember that so much of the area has been opened up since that time and many other dogs of all sorts have been introduced. However that's not to say that there are not still pockets where pure bred dogs do not exist. I'm sure that Dr Jo will bear me out there.

There are lines in the UK that go back to the original imports where apart from Fula of the Congo very few imports have been introduced. Therefore their genetic makeup is limited. However as has been already said their health has not deteriorated. I personally have always been able to maintain when I sold puppies that they would seldom need medical veterinary intervention between puppyhood and old age.

Unfortunately there has been such a preponderance of using studs merely because they do well in the show ring that the breed has changed here. I stick my neck out for the block in saying that poor breeding knowledge is resulting in the Basenji decline in the UK -nothing to do with a limited gene pool.

I can't speak for other countries. I think countries where breeding is only approved after prospective breeders have explained their reasons for breeding are producing 'better' examples of the breed.

Jo, I have just become a subscriber to Modern Basenji and so have only read Mary Lou Kenworthy's article and I do agree with her opinion on the establishment of separate breeding lines and am also in agreement with her on line breeding (and even in breeding)to establish these separate lines.

I am still trying to read Chris Maxca's article but don't seem to be able to open the link.

I'm still trying. Is the BCOA bulletin available on line? -

Voodoo, apparently the Canine Genome Project has established the Basenji as the oldest domesticated breed and also that many of the others so claimed have actually been reconstructed.

I'm still trying. Is the BCOA bulletin available on line?

From what I know, the Canine Genome Project only investigated 85 different breeds, so that doesn't seem like a really reliable way to find the absolute oldest breed. And 14 breeds came out to be the oldest, being the

Afghan hound, the Akita Inu, the Alaskan Malamute, the Basenji, the Chow Chow, the Lhasa Apso, the Pekingese, the Saluki, the Samoyed, the Shar Pei, the Siberian Husky, the Shih Tzu and the Tibetan terrier.Is this the bulletin you are looking for?

http://www.terrierman.com/BasenjiConservationBCOATheBulletinfinal.pdf -

@JoT:

FROM THE EDITOR by Wanda Pooley, published in the BCOA Bulletin magazine, Vol. XLVI, No. 3, July/Aug/Sept 2009, page 3.

Wanda did an analysis of the number of Basenjis registered in the AKC stud book over the 10-year period 2000-2009. The numbers she presents illustrate a steady decline and a difference of 47.47% between years 2000-2009. This indicates a shrinking population of breeding stock.Yes and no. I believe that there are just as many Basenjis born every year, perhaps even more now than there was 10 years ago. The decline in AKC registrations may be due to the following reason:

1.) There has been a steady increase in puppy mills and BYBs using disreputable registries such as the Continental Kennel Club instead of the AKC.

2.) Responsible breeders are using AKC limited registration and spay/neuter contracts.

3.) Public education has led to an increase in the number of pet owners who are eager to spay/neuter instead of breed.

WHAT IS DIVERSITY REALLY? by Mary Lou Kenworthy, published in The Modern Basenji Worldwide, Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 2011, page 3.

Mary Lou comments that,

"the main problem [she] noticed is that most people try to apply population genetics to individual breeding programs and cannot separate the two in their minds."

She is a proponent for breeders establishing separate breeding lines. She says,

"If breeders create and monitor their own lines, the breed, as a whole, will prosper. No breeder can maintain diversity by himself, and any attempt to do so will lead to disaster for the breeder and the breed. It takes a network of breeders working together with individual lines to maintain diversity."I agree.

IN DEFENSE OF BREEDING by Chris Maxka, published in The Modern Basenji Worldwide, Vol. 1, No. 1, Spring 2011, pages 6-7.

"A lot of good work has been done in many breeding programs, and we would not be helping the breed if we were to incorporate new imports with major flaws or of atypical type, for the sake fo the amorphous concept: 'diversity.' "I agree to a point. Every animal that is submitted to the BCOA for AKC approval must go through a process. It isn't perfect but it does give everyone the right to vote. Even if you do not agree with the majority decision, you still have the choice of whether to breed to them, their progeny, or to avoid them altogether. If a dog with numerous or serious faults somehow gets accepted, it is unlikely that people will flock to it for breeding. If they do breed to it, they will probably "bury" it deep in their pedigrees as fast as possible. By the time the animal is 4-5 generations back, it's conformational faults will have very little impact. (Assuming the breeder "has a clue", that is.)

-

From Dr Jo

When viewed globally, the Basenji metapopulation has a fragmented populace; those inside their native home in central Africa, here called the source population and those outside, here called the modern population. The source population is genetically diverse resulting in a low chance that any two negative genes will combine and individuals have a very high chance of being healthy. Conversely, the modern population is not genetically diverse and the chance of two negative recessive genes combining rises in direct relationship to the degree of homogeneity. The evidence that the source population appears to be "clean" is indicative that it is still diverse enough that negative genes are not yet combining.

Exactly. Thank you.

Okay, ding ding ding… precisely what I asked... and the article answered. 18 foundation dogs... doesn't that worry those of you who don't think we need a bigger gene pool?

Therefore, the Basenji modern population was derived from 18 original progenitors, with varying degrees of gene representation.

As a result of this very small pool of founders, some more heavily represented than others, the modern population of the Basenji suffered indiscriminate loss of genetic diversity. In response to the high degree of inbreeding and the lethal expression of some health related recessive traits, in 1990 the Basenji registry was opened to allow additional new founders (those whose genes contributed to future generations, leaving aside those which did not reproduce) imported from the source population in the Congo (Zaire). An additional eight dogs …This brought the founder number for the AKC registered modern population up to 26 contributors (see Table 2);From 18 to 26.. even with limited breeding, that helps. Or would have if all had been used a lot. The stats following that were daunting… one stud ending up with nearly all the contribution of Y.

Thus anything that limits the number of males in use drastically restricts the effective breeding population. Overuse of popular sires is a tremendous deleterious factor in genetic impoverishment.

And here we go to the bane of ALL breeds… popular studs. Truly, breeds would benefit if they limited the number of times a stud can be used. Instead we are freezing straws and using dogs dead many years. I always felt if a dog hasn't produced a son and grandson who can produce, thus replacing him, why would you keep using him?

You article is overwhelming. We have a basic 26, and need to TRIPLE that (50 to 100 foundation) to maintain health... yet each opening we bring in a handful?

-

I'd like to make some points in relation to items raised on this thread.

a) If we are satisfied that the the African dogs that have been added to the stud book are in fact African village dogs from the same isolated populations from whence our original Basenjis came from, then they are to me more true Basenjis than any else where in the world. They have bred, largely amongst themselves to survive African conditions and no doubt forage and hunt for their own food etc. Surely its up to us to educate our breeders and judges that perhaps our understanding of what a good Basenji is has shifted away from the African Basenji to now be the International Basenji?

b) Secondly someone made comment on the poor structure of the African dogs? Really - have they not looked at many of the dogs now gracing our show rings? Straight shoulders and over angulated rears seem to be the name of the game at the moment, throw in a few weak pasterns, undulating top-lines, unfit dogs and I really don't think the African dogs are any worse than our non African stock. A flashy side gait does not make a sound dog able to stand up to a life of finding your own food and no veterinary treatment, for a sore back after a lure coursing run. These African dogs are different maybe, but I sincerely doubt structurally worse.

With regard to adding in African stock I think it does some excellent things: - its starts discussion - we may not all agree but we start talking about aspects of this dog that feel are essential to it being a Basenji.

However I also find it interesting reading the Coppingers' 'Dogs a New Understanding', who are evolutionary biologists focussing on dogs and that they say that the 'Natural Breeds' are constantly shifting and changing in response to their environment, food sources, disease etc - and paraphrasing is that the type of dogs that were taken from African and called 'Basenji's' no longer exist, as their core population did not freeze in time, even if the Avongara and Lukuru pups are direct relatives to the dogs that were exported, they've been exposed to environmental pressures, periodic shifts genetic frequency which means that they are no longer exactly the same.

-

Dr Jo, I got to see Dexter this weekend. What a lovely boy he is. We who love this breed are living in exciting times for the next generations. IMO.

-

I have now read Chris Maxca's article 'In Defense of Breeding' and find I agree with much that she says particularly in regard to the knowledge required to breed. No doubt most here will have read the article but for those who haven't I quote - "Serious breeding requires a significant amount of knowledge of genetics, of the breed standard, and of the background of the proposed mating pair, their parents, their siblings, their parent's siblings, the grandparents and beyond. One should know the strength and weaknesses of the breed, have an idea what traits are dominant, what traits are recessive, and the heritability estimate of any particular trait." -

May I suggest that it is ignorance that produces a decline in any breed including our own? The introduction of other dogs bringing what they may to the breed won't of itself correct this ignorance.

Jaycee speaks about 'education of breeders and judges' but while I agree, I quote - 'there is none so blind as him who will not see'.

Robyn's posting - 'Even if you do not agree with the majority decision, you still have the choice of whether to breed to them, their progeny, or to avoid them altogether' - is certainly true Indeed in the UK when the acceptance of brindle into our standard was accepted on a very close vote only one or two breeders incorporated the colour and so they remain in a minority here.

-

My apologies for taking so long to return to this thread. My schedule and workload has kept me away from the Forum. I hope we can continue this discussion, which I think is very important.

Thank you for the gentle reminder that was sent privately.

To refresh my memory, I have just gone back and quickly skimmed through the discussion. Wow, so many good comments!

I am trying to attach a picture with my comments. Please bear with me …

-

I checked in the FAO's and see that it is possible to attach a file (a picture from my computer) to my post through the 'New Post' option. But, I don't see how to do that.

Can anyone explain how for me?

Thanks,

-

http://www.suite101.com/content/central-africas-dog--congo-origin-of-the-basenji-a224967

For this post, I have chosen to avoid using the label "Basenji" for the native dog because that serves only to distract and confuse people who get hung up on something that is no more than a Westernized word.

As a professional who continues to spend most of my adult life analyzing and studying the biomes of Africa and the variation of animal types across landscapes as well as living and working on the continent for 20 years, I would like to comment. I bring to this discussion a career of looking at the geographical distribution of animals at different taxonomic levels across Africa. Based on my extensive research, training, experience, and education, I thought we could look at this from a bit of a different perspective ... a perspective focused on selection pressures/ processes and the mechanisms / barriers that have regulated gene flow over the past 2,000 years (not including the recent 200 years), which includes ethnicity (tribalism), culture, language, geography, technology, logistics, history, environment, etc.

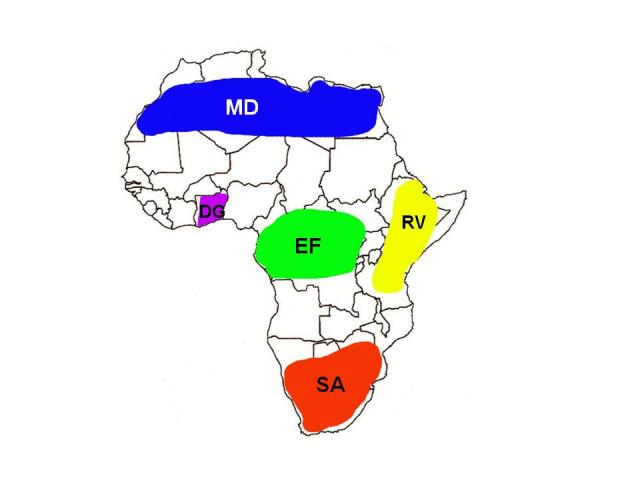

First, let's consider the geographic location of different biomes. A biome is simply any major ecological community of organisms, both plant and animal, usually characterized by the dominant vegetation. Biomes are defined in terms of the entire biotic community of living organisms and their inter-relationships with their immediate environment. To this end, I have attached an illustration of the most dramatic biomes of Africa that we might want to consider hypothetically for this discussion. These biomes have a direct and significant impact on the biotic (plant and animal types) assemblage available and the human lifestyles (including how the dogs are routinely employed) that evolved in each region.

The polygons illustrated are representative of some of the most distinct overall regional ecosystems on the continent :

MD = desert south of the Mediterranean ;

DG = Dahomey Gap ;

EF = Equatorial Old-growth Forest ;

RV = east of the Rift Valley ;

SA = Southern African countries.

All aboriginal (original or earliest known domesticated) dogs have a very similar morphology. The primitive canid body shape is known as the "long-term pariah morphotype" (LTPM). The LTPM silhouette is characterized by a "wolf or fox-like appearance, with sharp-pointed, erect ears, a long, pointed muzzle and a long, fish-hook shaped tail." This is the generalized form that is at the root of the domestic canine ancestry.

Before humans selectively bred for conformation, the earliest dog ancestor diverged into populations of separate types based on natural selection (including the mechanisms identified above) and their abilities to function in each biome.

Over the past few thousand years, each geographically specific variety of dog (with a distinctive common gene pool, consistency of type/ appearance, and consistent function) evolved from the basic / original LTPM form into a recognizable, visible type, landrace breed. The resulting distribution of general breed types are specific to their biome of origin.

This is one of the first points I would like to make. So often I read people referring to dogs that are "basenji-like" in that they have a common general silhouette.

What I believe they are actually observing is the LTPM starting place. It can be seen in all the primitive, aboriginal breeds : Australian Dingo, African Basenji, Canaan Dog, Carolina Dog, New Guinea Singing Dog, etc. But, "basenji-like" is NOT necessarily Basenji.

Given this background of landrace breeds specific to their biome, for the purpose of this discussion I can identify a unique type (breed) that will be called "EFb" (i.e., Equatorial Old-growth Forest breed) because it originates in the EF biome. EFb, as with the other landrace breeds, began with a primitive canid body shape thousands of years ago. Over those passing thousands of years, once the LTPM was introduced into the EF biome its form evolved into the distinct breed type recognized by early Westerners as the Congo Terrier (= EFb).

lvoss started this thread in order to discuss genetic diversity as it applies to the importance of adding Native Stock to our breed to provide "new genes." But, what do we really mean by needing to "add" genes to the breed (outside the EF biome of origin)?

One of the principal arguments for adding additional native stock to our registered breed is to expand / increase genetic diversity. But what does that really involve?

Possessed within the EFb population in their biome of origin we find the full breed complement of genes distributed across each individual EFb genome. Some individuals have some genes and others have others but together they have all the genes that make up the distinctive genetics of the EFb. It is that EFb genome at the population level that holds the maximum degree of genetic diversity.

Basically what we have is the wolf-dog common ancestor with the most diverse genome. As the population split / diverged, those that became the LTPM (primitive / original dog) had less diversity in the original genes (those from the wolf/dog genome) but added diversity through mutations, ect. As the LTPM were established in the various biomes, each discrete population diverged from the LTPM into distinct types associated with the biomes where they adapted to the regional conditions. Each of those types was genetically less diverse than the LTPM common ancestor but also gained "new" and different genes through the processes of evolution. [BTW, evolution through natural selection / natural processes does not happen over decades but requires thousands of years.] So, we ended up with different "breeds" (each consistent in type and with a distinctive population genome).

Side-track Note : Consistent in type is not the same as cookie-cutter phenotypic clones.

This can be illustrated with two examples.- A writer/photographer team from National Geographic came to my Congo base to write an article that had nothing to do with dogs. In fact, we had never even mentioned anything about the dogs. But, as we arrived in the villages, the NG team openly commented (without any prompting or even mention about dogs) : ?What breed of dog is this?? My astonished response was ?Why do you ask that (in those words)?? and they said ?They all look exactly alike!? Even laymen who have no background in the world of purebred dog breeds could identify the visible uniformity and consistency of type. But, they did not have the discriminating eye to distinguish the variation of individuals.

- Before we bred any of my native dogs, I had a long-time breeder visiting who has been breeding for several decades. They were very impressed with my dogs as purebred Basenjis. There was never any question about the purity of my dogs as Basenjis. The breeder spent many hours with my dogs, watching them and handling them intimately. When the breeder went home, they contacted me to tell me how taken aback they were after spending the day with my pack and then seeing their own conformation-show-line Basenjis, how much our breeding practices have made the breed into match-stick dogs, cookie-cutter clones.

Back on track : So a dog from the very heart of the EF biome would potentially contribute "new" (as in new to the Basenji gene pool outside the biome of origin but not new to the EFb gene pool) genes that are found within the original EFb population genome.

The question that the Basenji fancy must answer is do we want to add genes from any dog population across Africa which will potentially add "new" genes because other populations (for example, the MDb or DGb or RVb or SAb) have some different genes not found in the EFb ... essentially outcross to a different landrace breed. Or do we want to add genes from within the EFb genome?

Somebody said it already : We want new and diverse BASENJI GENES [the EF population genome]. That is the crux of it all.

If the fancy chooses to include any African dog that exhibits the LTPM silhouette because it offers different genes, then I agree that our breed will be no more than an African village mongrel and does not reflect its unique ancestry or origins. That is the choice the BCOA members must make.

And a related point that was made in this thread : sharronhurlbut asked, "Wouldn't the point of being able to add more, to allow folks who have gone to Africa or new folks to go, to check out different areas that maybe aren't open now?"

This is a critical statement. The value of adding additional native dogs to access other EFb genes only comes from adding dogs within the EF biome from areas not already represented by current founders. To continue bringing in dogs from the same geographic area(s) within the EF biome does not add "new" genes or contribute to gene diversity.

DebraDownSouth posted that we have 26 founders (as stated in my article published in 2007). However, since that article was published we have added 15 founders. So, we are now up from 26 in 1990 to 41 native dogs registered with AKC as Basenji breed founders in 2011. Of those 41 dogs (with varying degrees of representation in the gene pool), 20 come from the same area. That is contraindicated in the argument for adding gene diversity.

When we state the number of founders, the assumption is that each founder is equally unrelated to any other founder in the population except their descendants according to their pedigree representation. Our reference number does not take into account the degree of relatedness. There a mathematical calculation that can be used to determine the proportion of genetic material contributed to the current population by each founder by comparing a target representation with actual representation. Negative values denote founder over-representation. This requires that we decide what target level of representation is acceptable for breed preservation.

Has the breed changed since we established it outside its biome of origin?

My example above might suggest that we have now created a different (some might say "improved") phenotype. But, I would argue that does not take into account the full spectrum of AKC registered Basenjis that do not appear in the conformation show ring.

Further, I think it is very important for us to consider whether the Basenji at the source (the EFb, for the sake of this discussion) has changed. Here I refer you to pictures from the website linked in my signature line. On the Lukuru Basenji Conservatuers website home page there is a black&white picture of my four native imports in 2009 and a comparable black&white picture of five "Of the Congo" dogs in the late 1930's. Even after 70 years, it is striking how similar my native imports resemble F1 generation from the original imports. In fact, both my husband and I had to take second and third looks at the old picture because it looks so much like our dogs. In this case, I think the evidence indicates that in some areas within the biome of origin the EFb of today is uniform and consistent with the EFb of yesteryear when we first established the Basenji as a registered breed.

-

The numbers I have seen done by people in the breed shows that we have lost roughly 50% of our founders. That includes just from the new imports in 87/88, which is only just over 20 years ago, and already we have lost 50% of them and some only trace back to one or two breedings or 1 or 2 offspring.

This brings us back round to Clay's point, what good is it to open the stud book to foundation stock if there is no longer plan for incorporating them into the gene pool. If BCOA wants a successful native stock program then it should also include educational opportunities to learn how to best make use of the native stock otherwise people will just dip in once and then breed away from it and get the "feel good" sensation of doing something good for the breed when in fact they have done nothing.

Genetic diversity in the Basenji breed has long been an issue that interests me. I have often wondered what is really happening in our breed to reduce gene diversity? Does bringing in additional native stock actually impact the gene diversity of the breed?

lvoss has been asking similar questions in this thread.We know that historically the Basenji breed has suffered significant bottlenecks that contribute to loss of diversity in the gene pool.

In the first 25 years of the establishment of a breed we call Basenji (between 1936- 1961), 18 individuals who contributed unequally to the gene pool were the foundation of the breed (9 dogs & 9 bitches). Three of these were outcrossed Liberian camp-dogs. The record reveals that the Liberian camp-dogs were subjected to a controlled breeding program for more than 12 years selecting for "Basenji" traits. Only then did the get of this intensive selection effort become recognized as outcross founders. In fact, the results of the breeding program produced dogs that were exported to Zambia to be bred with purebred, registered Basenji bitches (bred down from Congo native stock) brought from England. Then those get were imported to England by Elspet Ford and to the USA by Gwen Stanich. Although they are considered to be native dogs because they were whelped in Africa, they were actually only a percentage African stock.

There were no Liberian imports (native Liberian dogs) registered as Basenjis. By the time the dogs were imported, they were heavily blended with Congolese dogs BEFORE the progeny were included in the breed registry. This outcross was done simply because some members of the fancy wanted the dominant black coat color. Once the dominant black & white was bred with Basenjis from England, there were never any back-crosses to native Liberian stock.This is a perfect example of the comments by lvoss. Her important premise is that in order to have a significant impact, new dogs have to be desirable to breeders and the fancy. They have to contribute something positive to the breed. In the example of above, the contribution from outcrossing to Liberian dogs was the dominant black coat color.

Similarly, the example of the Congo dogs registered in 1990. The contribution they made to the breed was the brindle coat pattern. Although subsequently we can say that they also provided new breeding opportunities to steer away from fanconi; we did not know that when the dogs were imported and that was not a goal of the importation effort in 1987/1988.Anyway, the founder effect severely reduced the genome (frequency of genes in the population) of what had been the genetically diverse EFb geographic breed.

Drastically narrowed, only the genome of the dogs used to start the breed served as the genetic foundation of the dogs named Basenji by Westerners. In this way, a gene quite rare in the EFb population may have a much higher frequency in the Basenji population; conversely, genes common in the EFb population may be infrequent or even absent from the Basenji population. We can never know what we lost or what we disproportionately magnified in the genome of the Basenji compared to that of the EFb.Of course, that wasn't the end of the story nor was the door closed on including other EFb genes. In 1990 and in the recent two years, additional native dogs have been added to the foundation gene pool. But, the Basenji genome is still based on a small number (subset) of individuals and can never represent the EFb genome.

Several years ago a breeder interested in finding unrelated lines to use with her own line did a pedigree analysis. By studying a sample of dogs that might be of interest and were "unrelated" to her own lines, she found three significant bottlenecks and extrapolated her findings to the wider gene pool of the breed.

First, from her sample she concluded that the US Basenji gene pool was approximately eight significant foundation individuals. The foundation stock who had contributed most to the breed were :

Bongo of Blean (male)

Amatangazig of the Congo (female)

Bereke of Blean (female)

Kindu (male)

Kasenyi (female)

Fula of the Congo (female)

Bokoto of Blean (female)

Wau of the Congo (male)

Second, Basenjis in the US show a second significant genetic bottleneck through disproportionate use of the OTC suffix (Of the Congo) dogs. During World War II Veronica Tudor-Williams was foremost in preserving the breed at a time when the Ministry of Home Security required the compulsory destruction of all dogs. There were a handful of other breeders that maintained lines, but it was VTW who bred prolifically and exported her OTC dogs to the USA.

Third, Basenjis in the US had a significant genetic bottleneck in the 1960's and 1970's due to the use of three popular sires, two of whom were sons of the third.Without knowing about that analysis, a number of years ago I inquired about the Basenjis that were used as the basis to make conclusions about the Basenji Genome in all the genetic research into breed origins. From that information I was able to determine that genetically Basenjis are derived (for the purpose of research) from only six founders :

three foundation sires -

Avongara Gangura

Kindu

Wau of the Congo

and three foundation bitches -

Avongara N'Gondi

Avongara M'Bliki

Amatangazig of the CongoAnd a couple years ago I initiated a game on one of the Basenji chat lists to track tail male and tale female lines. This was a simply and fun exercise to illustrate a singular aspect of founder loss in our current population (it does not reveal what is happening in the middle of a pedigree nor loss of genes on the autosomal chromosomes). So, it does have limitations. But it can reveal when a founder no longer has descendants; i.e., the founder is lost to the breed and all the unique genes the founder contributed. At that time it appeared to me that there were quite a few breeders who believe that each kennel name represents a distinct genetic line. The exercises was not only fun and easy with minimum instruction, but it illustrated to many that genetic diversity is NOT determined by the number of kennel names.

These examples give us important insight into the use of native stock in our breed; the overrepresentation of individuals in the breeding program, loss of some unique breeding lines, and illustrate how much our gene pool has narrowed.

Concerning the erosion of the gene pool, it is important to know how many founders are still represented in the current Basenji population and to consider the number of generations our current dogs are away from the founder. In genetically limited populations, a certain amount of unique genetic diversity is diluted with each reproductive event through the action of genetic drift, inbreeding and artificial selection. Thus, the number of generations away from the founder becomes an issue of concern. Genetic material can be rapidly narrowed, each generation carrying a reduced level of heterozygosity as it is permanently linked by the horizontal pedigree. The average time between one generation and the next is a convenient yardstick to help us realize the relative rate of genetic attrition.So, I still wonder if admitting new native stock EFb into the Basenji gene pool will actually help gene diversity in the long run.

I keep going back to the article by Mary Lou Kenworthy, "WHAT IS DIVERSITY REALLY?" (The Modern Basenji Worldwide, Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 2011, page 3) and Mary Lou's statement, " If breeders create and monitor their own lines, the breed, as a whole, will prosper. No breeder can maintain diversity by himself, and any attempt to do so will lead to disaster for the breeder and the breed. It takes a network of breeders working together with individual lines to maintain diversity. "

I think she is correct.

-

Jo,

Thanks for taking the time to provide so much thought provoking detailed information. I almost missed a meeting because I was so engaged reading all of it, lol. I know I have several questions but I'll have to wait until after work to ask them.

Clay

-

Jo,

Thanks for taking the time to provide so much thought provoking detailed information. I almost missed a meeting because I was so engaged reading all of it, lol. I know I have several questions but I'll have to wait until after work to ask them.

Clay

Thanks Clay! Just in case your computer presented my two posts on different pages … I posted two long comments this morning. The first with an attached figure appeared on page 6 of this thread and my second this morning appeared on page 7.

-

I know the situation is different in the UK but I find this thread extremely interesting and of course much applies to our UK population.

I am having to print your posts - for my own information - Jo because I find it difficult to read off a computer - I hope I have your permission?

-

I am having to print your posts - for my own information - Jo because I find it difficult to read off a computer - I hope I have your permission?

Yes. Of course.